By Hernan Colmenero

Badger Creek Ranch is a special place. High above the Arkansas River Valley in Central Colorado, guests can stay on a working cattle ranch rimmed by 14,000-foot peaks of the Rocky Mountains. A team of men and women on horseback tend these lands, forming a long chain of stewardship dating back to the people of the Ute, Jicirilla Apache, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Pueblo, Shoshone, and Comanche Tribes. Ranch owners Chrissy and Dave McFarren see to it that their legacy is one of regeneration and caring land stewardship, where a vibrant community is nurtured now and for generations to come.

Badger Creek Ranch LLC has ambitious goals. The ranch team is restoring riparian areas to catch, slow, and retain more rainwater. They work to reduce erosion by various methods, including carefully planned regenerative grazing with cattle.

By partnering with Full Circle Alliance, their closely affiliated nonprofit, Badger Creek Ranch fosters success for the next generation of land stewards. They create community by articulating the importance of regenerative agriculture to customers at the farmers markets where they sell their meat. Community is fostered, too, through learn-while-doing events, such as the building of Zuni bowls, erosion control structures that use rocks, water, biology, and time to heal the soil sponge. Partnerships with Audubon Society and Central Colorado Conservancy help the ranch team restore and conserve these lands, promote wildlife diversity, and at the same time, generate a feeling of kinship between community members and the land they inhabit together.

With access to water being the limiting factor for rangeland grazing in semi-arid West, Badger Creek Ranch has designed a new stock-watering system with the help of National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). This water point project will allow further restoration of the lands through rotationally grazing cattle in areas that currently don’t have access to water. A watershed restoration group has helped with drilling a well. NRCS engineers designed the stock watering system, and NRCS staff provided a grazing plan that ensures cattle will always have access to water without damaging riparian areas. Before this project, Badger Creek Ranch staff (and adventurous guests) would push cattle out of the riparian areas on horseback because there were only two water points on the 8,000-acre ranch.

With access to water being the limiting factor for rangeland grazing in semi-arid West, Badger Creek Ranch has designed a new stock-watering system with the help of National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). This water point project will allow further restoration of the lands through rotationally grazing cattle in areas that currently don’t have access to water. A watershed restoration group has helped with drilling a well. NRCS engineers designed the stock watering system, and NRCS staff provided a grazing plan that ensures cattle will always have access to water without damaging riparian areas. Before this project, Badger Creek Ranch staff (and adventurous guests) would push cattle out of the riparian areas on horseback because there were only two water points on the 8,000-acre ranch.

The project includes installing a solar-powered pumping station at a well, which feeds into two 5,000-gallon storage tanks. From there, buried pipelines distribute water to dedicated paddocks. Scattered along the pipelines are hydrants to fill water troughs, which can be moved from one paddock to the next to accommodate the grazing plan.

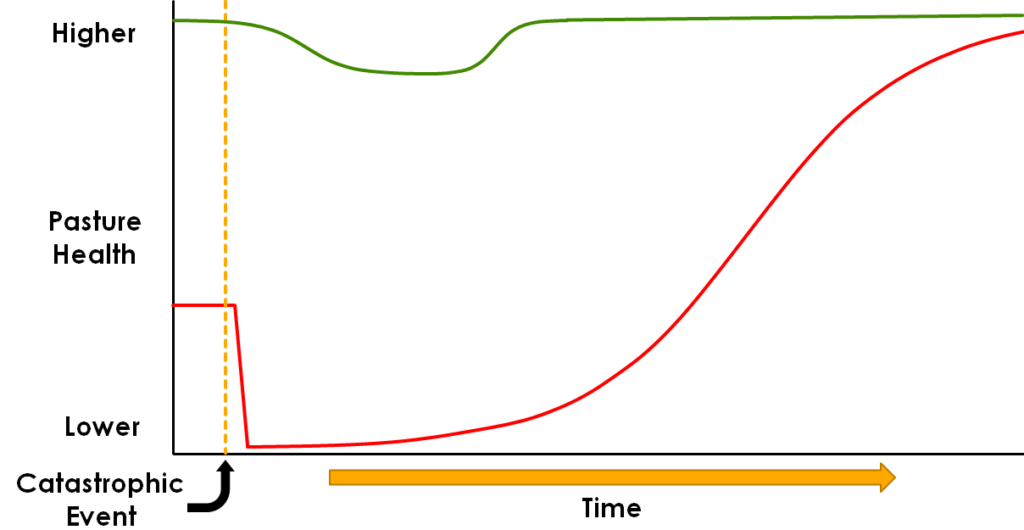

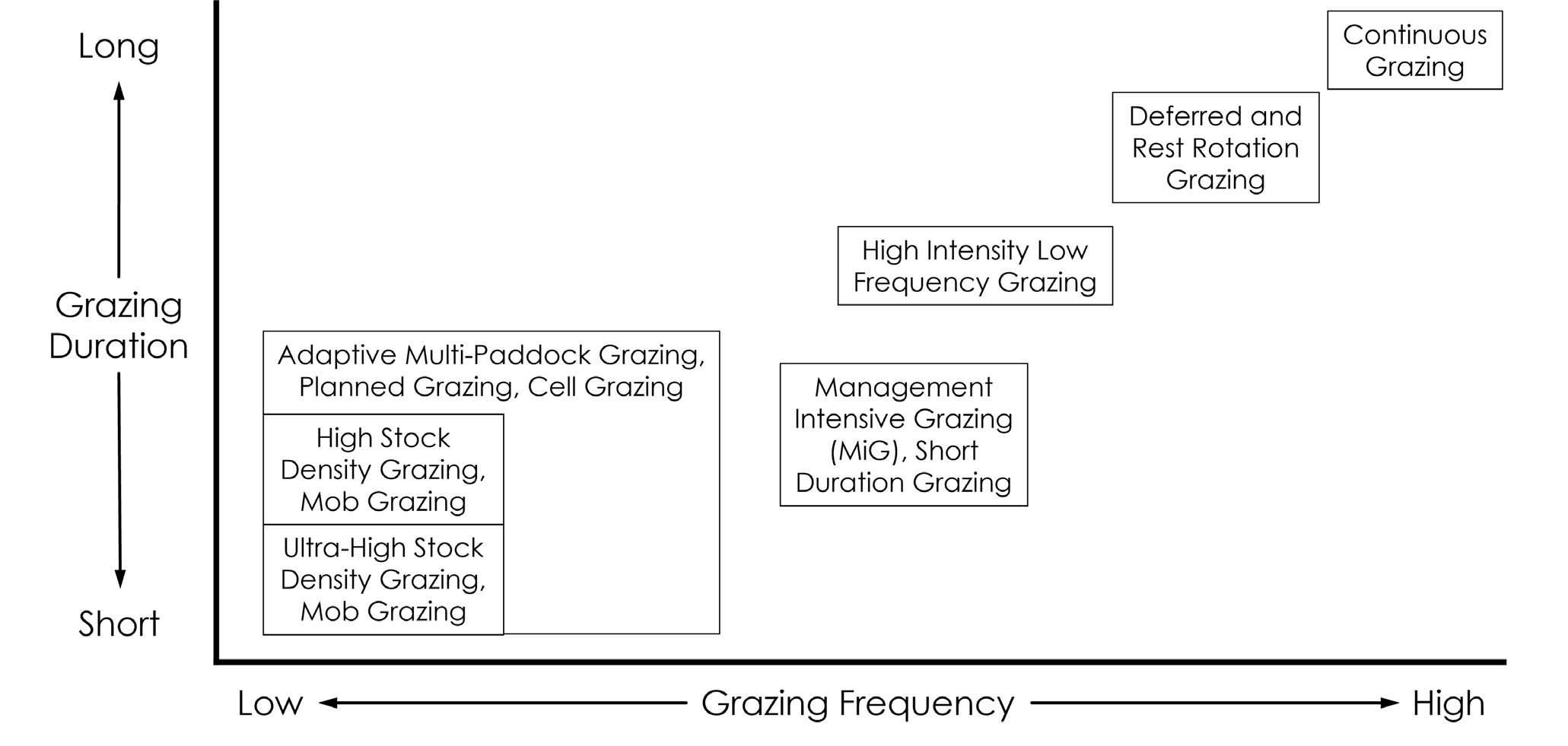

Currently, this set-up is being trialed on the Badger Creek Ranch horse herd. If it is demonstrated to be feasible, this operation will be scaled to include the cattle herd and other animals. If and when this approach is replicated across the ranch, land that is currently degraded and without access to water could be regenerated through carefully managed mob stock grazing, which optimizes plant health, adds essential nutrients, and stimulates the soil microbiome.

Managed correctly, this method will save time in rotating cattle, and the efforts will be aligned to the ranch’s philosophy of low-stress stockmanship. It will help, too, with regeneration of nutrient-dense perennial forage and with the restoration of riparian areas. But special attention will need to be given to the fencing of the paddocks with new water points. Where new water points are being put in, the ranch is also installing metal piping fencing, which creates a strong fence where cattle can come to drink. This keeps them where they are supposed to be, saves time in fence repair, and is safer. With higher concentrations of animals, old post and barbed-wire fencing may not hold up. Rough terrain and lack of roads make it difficult to repair fences and the stock watering system, but close monitoring of the land and animals, endless persistence from the team, and a bounty of hope keep the ranch strong.

When asked whether the addition of cattle and rotational grazing on the range has been worth the hard work, Chrissy gives an ecstatic yes! It is hard work, she says, but the “joy [of] working out on the land every day and watching it through the eyes of friends and guests has been great.” The ranch team is looking for ways to further strengthen their community.

Farmers and ranchers often toil in silence and the ag community at large may not understand the full menu of challenges, opportunities, ideas, and resources available. The Soil for Water Network aims to bridge that gap by connecting producers to one another and to practices that promote soil health and water retention. For established and beginning producers alike, Chrissy urges thinking about building bridges in their community, to “keep fighting the good fight, without fighting [each other].” She advises us all to stay connected to others who share a passion for the land, so we may do what is right for it and for ourselves.

Find Badger Creek Ranch online to learn more: