By Justin Morris, NCAT Regenerative Grazing Specialist, and Lee Rinehart, NCAT Sustainable Agriculture Specialist

Field ready for haying or grazing. Image: Steve Slater, via flickr

Do you like to eat fresh food? Do you like variety in your diet? Most of us would probably answer ‘yes’ to both questions. Not surprisingly, livestock crave the same things we do. If that desire is not met, then we get less than optimal livestock performance. This can create health problems for the animals, increase costs, and reduce profitability. So how can we constantly provide fresh food for livestock and a diet that is diverse? That’s part of what we address in the third session of the National Center for Appropriate Technology’s (NCAT) Advanced Grazing for Regenerating Soils and Enhancing Animal Nutrition webinar series.

Improve Plant Diversity Including the Use of Forbs, Shrubs, and Trees

This session begins with a discussion on the major and minor chemical compounds of plants that affect animal performance and health. The major, or primary, compounds include carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. While these compounds make up most of what is found in the meat and milk that livestock produce, the secondary compounds, while dramatically less in amount, are no less important. These compounds consist of the alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, and sulfated amino acids. What is the purpose of these compounds? They promote liver health, are anti-parasitic, anti-amoebic, anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer. Many of our broadleaved, flowering plants, shrubs, and even trees have significant quantities of these secondary compounds, which is why plant diversity is so important. Farmacy on the pasture!

Use Grazing Durations that Allow Livestock to Get Fresh Forage Frequently (Daily if Possible)

Research has shown that the amount of forage livestock consume is highest when the grazing duration is just one day. When livestock spend two days in a paddock, their forage intake on the second day is less than it was on the first. If livestock spend five days in a paddock, their forage consumption on day five is half that of day one. Why? Because on day one, animals eat the most palatable plants in the pasture. On day two, livestock eat the second-most palatable plants. The longer livestock remain in a pasture, the more time they spend looking for highly palatable plants, while trying to avoid plants that have been stepped on, laid on, and fouled on. This results in animals eating less, which in turn decreases weight gain and milk production. Moving livestock every day to fresh, highly palatable pasture encourages them to eat more for higher weight gains and milk production.

Use Light to Moderate Grazing Severities So Livestock Get the Highest Energy and Protein

Forage tests have shown that energy and protein are highest in the top of the plant and lowest at the bottom. The higher the energy and protein content of a forage, the more weight livestock can gain and the more milk they can produce. And livestock tend to graze plants from the top down, even grazing seedheads before leaves if plants are in the early reproductive growth phase. Parasite re-infection can also largely be avoided, as livestock graze the top of plants in either the elongation or reproductive growth phases. Using short grazing durations and light to moderate grazing severities allows livestock to get just one bite and move onto the next ungrazed plant. This also helps the plants to recover faster from grazing!

Wait to Turn Livestock into a Field or Paddock Until it Looks Like it Could be Hayed (Late Phase 2/Early Phase 3)

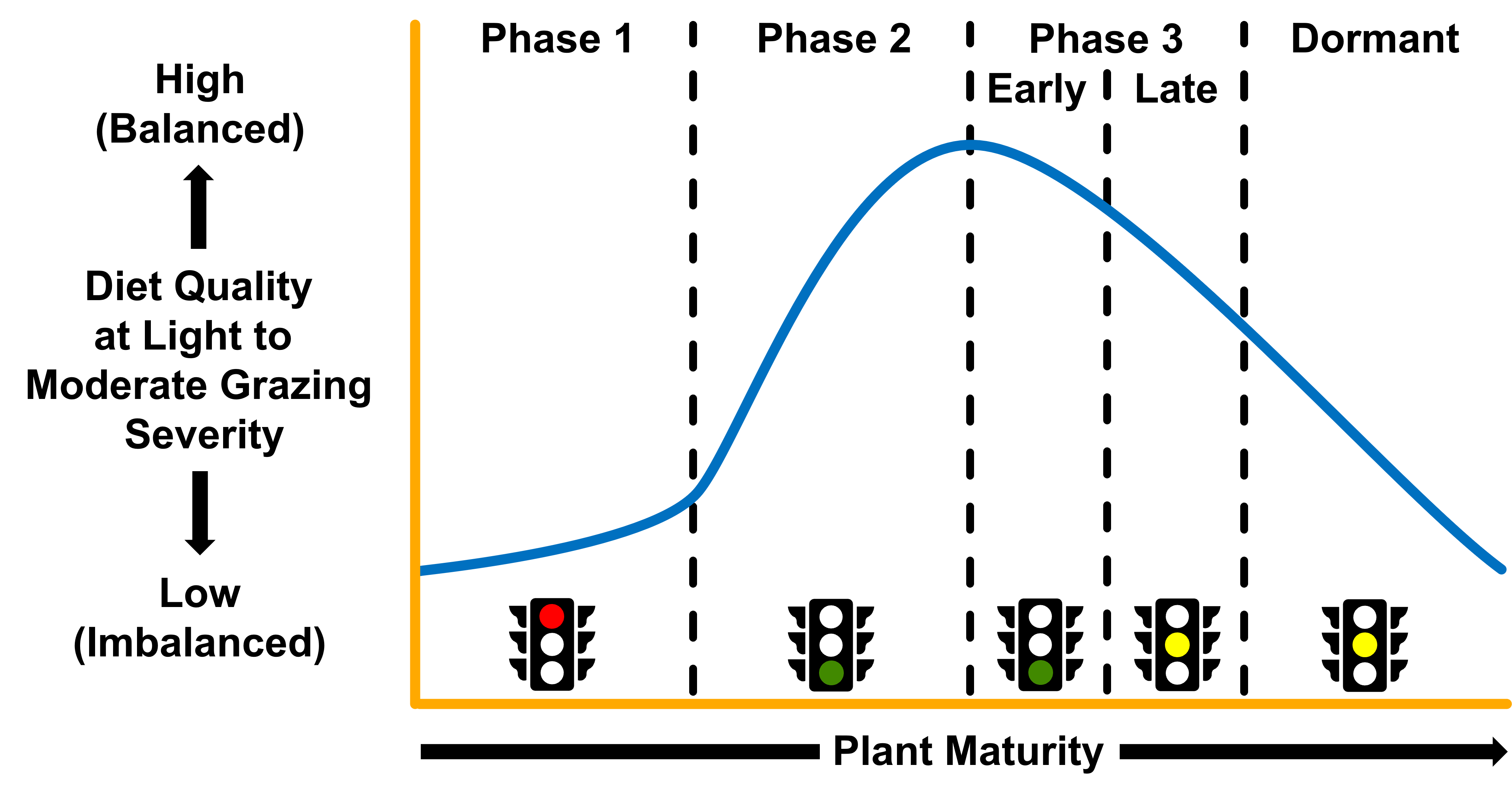

Livestock grazing vegetative plants creates overgrazing problems for the plant and an imbalanced diet for livestock. Livestock require the three primary components of energy, protein, and fiber. An excess or deficiency in any of these three components creates dietary imbalances, which can affect animal health and performance. Plants in the elongation growth phase (phase 2) or the early reproductive growth phase (early phase 3) have the best balance of the three primary components for best rumen function (see Figure 1). Plants in the vegetative growth phase (phase 1) have an excess of protein relative to energy and very little fiber. This can create metabolic issues for livestock, which can result in high blood urea nitrogen levels, reduced fat reserves, loss of body condition, lowered weight gain, loose stools, infertility, and suppression of the immune system. Grazing more mature plants provides a more balanced diet for livestock, which can improve animal performance.

Figure 1: Diet quality of livestock grazing plants at different maturity stages. Traffic light colors indicate whether to stop grazing or don’t graze (red), graze with caution (yellow), or graze (green).

Focus on Animal Behavior, Rumen Fill, Urine pH, Manure Scoring, and Forage Quality Tests to Ensure Livestock are Getting Enough Quality and Quantity

A grazier can use several different indicators to determine whether livestock are getting a high-quality diet balanced for energy, protein, and fiber, as well as enough quantity. Here are some indicators that forage quality and quantity are not meeting livestock nutritional needs:

1. Animals are anxious to enter the next paddock and immediately drop their head to begin grazing at the paddock entrance

2. Rumen is sunk in

3. Urine pH greater than 7.0

4. Manure score that is very runny (score 1 and 2) or very stiff (score 5)

5. Digestible organic matter to crude protein ratio that is either less than 4:1 or greater than 7:1 (4:1 is optimal)

Use Appropriate Paddock Shape and Animal Movement Strategies to Improve Animal Performance and Landscape Health

The webinar concluded with a brief discussion about how paddock shape and livestock movement influences forage intake, trampling effect and manure/urine distribution. While individual animal performance on a per-head basis is generally high initially for large pastures that will hold livestock for several weeks or months, animal performance per acre is low because there are relatively few livestock over the whole pasture area. Subdividing fields into progressively smaller and more numerous paddocks where stock densities (the relative closeness of livestock to each other) are quite high and grazing durations are just a few days or less in any one paddock can provide high animal performance if a light to moderate grazing severity is used. This strategy generally provides the highest animal performance on a per-acre basis.

With portable electric fencing and portable watering systems, there are numerous ways to improve forage intake. Figures 2-5 illustrate just one example.

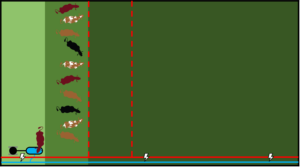

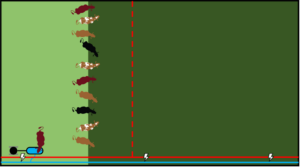

Figure 3 (Step 1): To move livestock to the next paddock, the primary polywire is rolled up and livestock walk forward a few steps to fresh pasture as the grazier passes by.

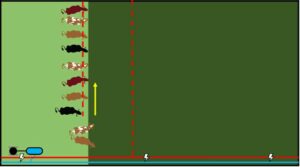

Figure 2: Red dashed lines are portable electric fences composed of single-strand polywires. One polywire is directly in front of the herd (primary polywire). Another polywire is placed to form the far side of the next paddock (secondary polywire), which also contains livestock should the primary polywire be breached. Water trough and salt/mineral feeder are mounted on skids to be portable.

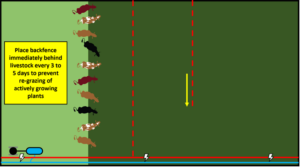

Figure 5 (Step 3): The previous primary polywire is being unrolled (now the new secondary polywire) and reconnected to the electric fence at the bottom of the figure. The next paddock is then ready to go for the next move.

Figure 4 (Step 2): The primary polywire is completely rolled up. All livestock advance into the next paddock.

The final session of this series will be held on June 9 at 5pm Central time. Register here.

Watch previous sessions here: Session 3, Session 2, Session 1.

Related ATTRA Resources:

Grazing for Resilience: Bouncing Forward from Catastrophic Events

Pasture, Rangeland, and Adaptive Grazing

Pastures: Sustainable Management

Why Intensive Grazing on Irrigated Pastures?

This blog is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.