By Lee Rinehart, Sustainable Agriculture Specialist

“If you always leave grass behind, you never run out of grass.”

I was going to save this quote for the end of this article; when I heard it during our conversation, I knew it would nicely summarize Guille (Gil) Yearwood’s philosophy. Now, I think it’s better to start with this quote. It’s an observation he had, “one of those moments,” in his words, back in the 1980s when he began his transition from continuous grazing to a rotational system. “I’ll never forget that day years ago when I went back to a grazed paddock a week later and saw regrowth.” It was something he’d never seen before. “When you graze a pasture continuously, you have no idea how much grass you have because its continually disappearing.” After Guille switched to rotational grazing, his paddocks would look like a hayfield four weeks after grazing. This, in his words, “is totally different and totally better.”

Guille Yearwood has been ranching forever. He started during his teenage years—1975 to be exact—and has been raising cattle ever since. When he started, he had other businesses going as well as the cattle work—25 years in real estate for one—but Ellett Valley Beef Company has been his full-time job since 2008.

Ellett Valley Beef Company encompasses seven locations around Blacksburg, Virginia, mostly on leased property, on which he grazes seven groups of South Poll beef cattle—a total herd of around 350 animals. Back when he first got the rotational grazing bug, by paying attention to Virginia Tech’s rotational grazing research, Guille divided his pastures into eight or 10 paddocks and began grazing stockers through the rotation. This is when he had his “aha” moment. He saw his forage yield increase immediately, and though the gains per head were not what he was used to, he noticed a higher herd weight gain because he could easily increase his stocking rate. Guille realized this new system could be taken up a notch, and now has 80 paddocks spread across all his pastures.

Cows grazing fescue – Oct. 2021

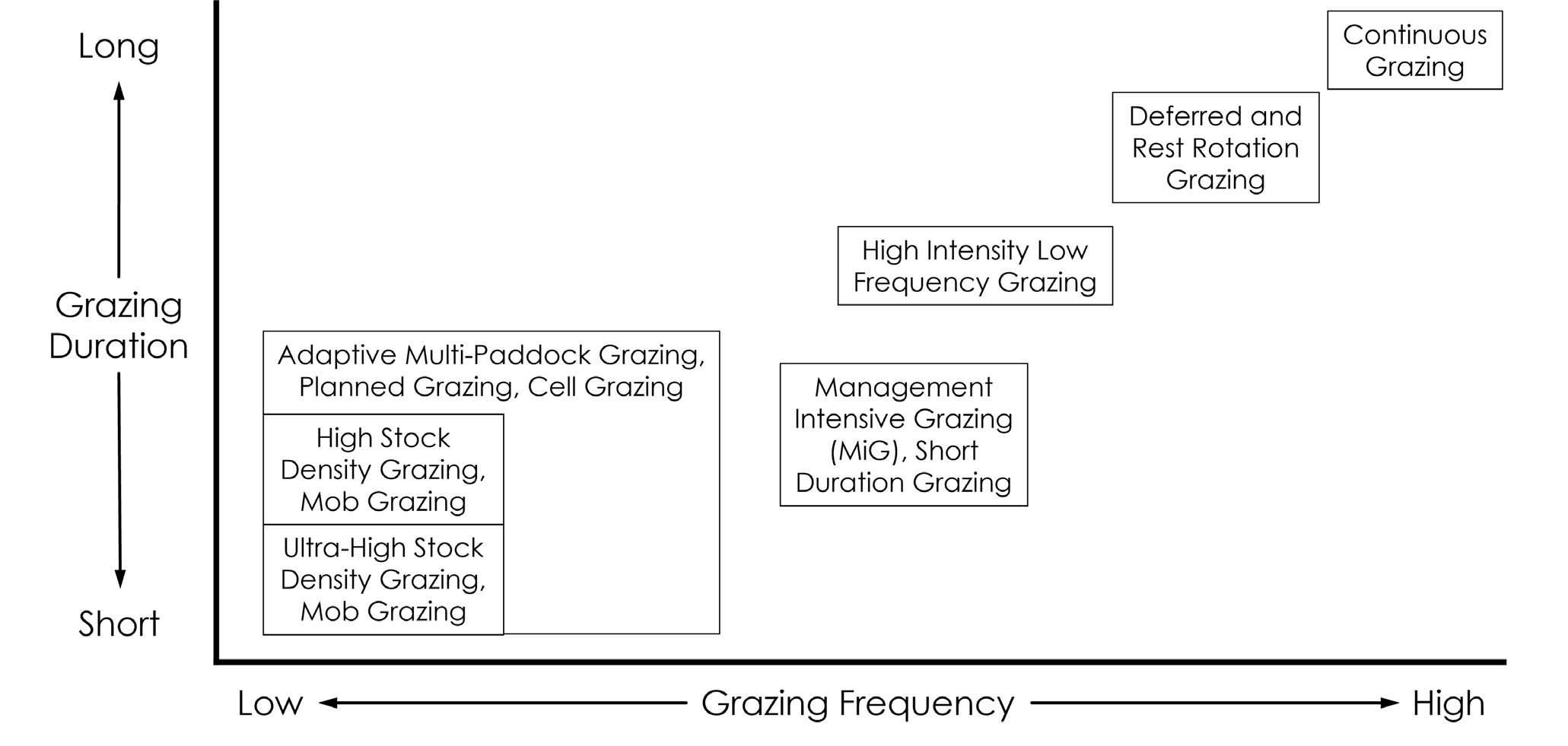

Guille would travel up to 90 miles a day checking and moving cattle before he reduced the number of leases a few years ago from 13 locations. Now, they’re all closer to home, significantly reducing the time to check and move cattle. Now, he and a part-time hired hand can check and move cattle more efficiently. He relies on grass alone and follows adaptive management techniques with frequent moves, mostly daily, and recovery periods of seventy to ninety days to allow for full plant recovery before the next time cattle see the paddock. Guille considers his system to be truly regenerative. In fact, he started regenerative grazing long before term came about, and he’s glad it did “because it’s a good term.” It accurately describes his way of doing business. His regenerative practices include highly diverse pastures, grazing for animal impact and nutrient cycling, and long recovery periods for plant rest and accumulation of high amounts of organic matter to the soil.

Ranch Profitability

“To be profitable, I need to graze all year, if possible,” Guille noted. His goal is to produce excellent grassfed beef and be profitable, and to accomplish that, his focus is on grazing as many cattle as he can through the winter. Some time back he began thinking about return on investment and started looking at the farm this way, realizing he needed to run this like his other businesses. He did an economic analysis and a budget and figured out that he couldn’t afford fertilizer or hay equipment. “I saw that [buying fertilizer and making hay] would not make a profit, so I got rid of them.” Instead, Guille buys hay to cover the 40-65 days during the year when he needs it. For the remainder of the year, the cattle graze fresh and stockpiled pasture. In fact, the interest he received from selling his hay equipment covered his hays costs, and he’s never looked back.

Guille’s pastures have been fertilizer-free since 2000. Prior to transitioning off of fertilizer, he had broadcast clover for several years, as he was particularly concerned about nitrogen fertility. But the second year after stopping nitrogen applications, he fertilized a fescue pasture in August, a common practice for preparing fescue for winter stockpile. However, after comparing days of grazing data between this and the prior year when no fertilizer was used, he realized he lost money with the fertilizer application. The days of grazing were the same for both years. This was the end of Guille’s use of purchased fertilizer. The diversity of his pastures, which included legumes and grasses, coupled with his adaptive management, provided the nutrient cycling and carbon sources he needed to be sustainable without it. All the while, he was ratcheting up his grazing techniques, trampling residue, and feeding hay on land that needed the nutrients. It seems that when he decided to go fertilizer-free, he had already been taking care of the soil for years, so he was ready.

Educational Philosophy

Guille’s college work includes an English degree from Virginia Tech and a master’s in English from Rice University. It is easy to tell from reading the blog entries on his website that his liberal arts education sharpened his critical thinking skills and gave him a foundation well suited for the complexities of agriculture. Since then, he has been inspired by Joel Salatin, especially his book Salad Bar Beef, which he says had a big impact on his philosophy. Other luminaries that inspired him include Andre Voisin, the “first true scientist that addressed rotational grazing,” Newman Turner, Jim Gerrish, and Allen Williams, who “has it figured out and is backed up with real science.” He learned about brix levels in forages from Williams, and though skeptical at first, he has seen a tremendous difference by moving cattle to new paddocks in the afternoon when brix levels are highest. Guille has learned so much and, with a natural drive and desire to help beginning and transitioning farmers, has much to share from his experience.

“The big challenges a new farmer needs to overcome are the tactile, physical problems. These are harder for people to pick up than we realize. For instance, a polywire reel is a foreign object to a beginner, but for me, it is an ordinary tool like a screwdriver.” Guille helps beginners by simply taking them out and involving them in moving cattle, checking cows, or moving polywire, and showing them how to shut off the power, tie polywire, or set posts. Newcomers are fascinated by the complexities of grazing tools and procedures, and he has come to understand how new this is to some people, so he trains people from this tactile perspective. Also, new farmers don’t know cattle and it’s a long learning process. His advice is to read all the books you can at night and during day go to the stockyard. Seriously, the stockyard. When a cow comes into the pen, evaluate her breed, condition, and weight, and especially listen to the people talking around you and pay attention to what they are observing.

“Some things we are just going to battle,” he said. For instance, weeds in fence lines are a major struggle for Guille. He has miles of electric fence and keeping them maintained is labor-intensive. He can spray a lot of fenceline in a short amount of time but would rather not use herbicides, and some lessors don’t want him to spray pesticides. “Weed eating would occupy me all summer, and then there’s the yellow jackets!” It’s an ongoing struggle, and he makes it clear he doesn’t have all the answers. “On this ranch you’ll see a lot of mistakes,” he said, but he has learned more in the past four years about grazing than in the 10 years preceding it. “Don’t panic… just try it” is the best advice he can give. “Don’t be afraid to set the field up and try it; if it doesn’t work, adjust and move on.”

Fine Tuning and Adaptation

Pasture with johnsongrass, fescue, clover, and stickweed (Verbesina occidentalis).

Guille doesn’t farm his land. Rather, he follows the truly regenerative practice of grazing what is available with one-day grazing periods and 70- to 90-day recovery periods. Plant communities change seasonally and yearly as different (adaptive) grazing practices are employed on the land. His pastures are diverse and include johnsongrass, which many graziers have tried to eliminate but he sees as complementary to his grazing system. Johnsongrass has usually been found in bottom land but now it’s moving on to upper lands, places he has never seen this hardy perennial grass before. It works out well in his grazing system because by the time he gets around to a paddock with johnsongrass, it’s fairly mature so it has no prussic acid problems. Also, there is enough diversity in the pastures and grazing them before the frost works well in his rotation.

Guille’s adaptive management hits a high note when it comes to finishing steers on grass. When trying to finish a group of steers (get ready, this is brilliant), he mimics continuous grazing (which, though hard on the pasture is good for optimizing individual animal gain) to allow the animals to exhibit more grazing selectivity. He keeps the rotation going at about the same grazing and recovery periods but gives the feeder steers bigger paddocks. “I’ve measured these results. On excellent pastures with medium-frame cattle, one group gained 4.2 pounds over six weeks and another group gained 4.6 pounds.” If a normal paddock size is a half-acre, he gives the finishers an acre and a half for the same period, giving them the ability to be more selective in their grazing.

Guille Yearwood currently serves as Farmer Advisor for the Virginia Soil for Water Project and is working with the Virginia Association for Biological Farming to plan a field day on his ranch in the spring of 2023, where participants can see up close the practices that he has been refining for the past 50 years. “This is the best job in the world,” Guille noted at the end of our last talk. His passion for the land and grass-based agriculture is palpable, as you’ll see if you make it to the spring field day. And, oh yes: Guille is an excellent writer, with a witty humor and deep love and knowledge of his subject, as you can see from the blogs posted on his website.

Related NCAT Resources

Soil for Water – Working to catch and hold more water in our soil

Pasture, Rangeland, and Adaptive Grazing – ATTRA (ncat.org)

Other Resources

EVBC Grassfed Beef (ellettvalleybeefco.com)

This project was based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2020-38640-31521 through the Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program under subaward number LS21-345. USDA is an equal opportunity employer and service provider. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

This project was based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2020-38640-31521 through the Southern Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program under subaward number LS21-345. USDA is an equal opportunity employer and service provider. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.![]()