By Hernan Colmenero

To understand something, we must be willing to observe it. Observe the movements, patterns, shapes, and textures of the thing. The distance, frequency, timing, and sizes, too. Determining soil health and water-retention capacity is no different and requires observation. Doug Garrison has been doing just that for 25 years in Malcolm, Nebraska. Using a “fresh grass and move” management technique, he has been comparing pasture forage production when compared to prescribed burning. The results are unquestionable.

Growing up in Lincoln, Nebraska, Doug often visited his grandparents’ farm and grew to appreciate the animals and the outdoors. When he took over his current land in 1997, he tried a prescribed burning technique to reset the plant community and manage it. Much of the land was previously in old native prairie, trees, and a creek. Some of it was old farmland. After encountering health issues, he found grassfed beef to be a healthier alternative to conventionally raised beef. You can view some of that data here and here. Realizing that the whole ecosystem starts in the gut of the cow, he brought in 10 heifers and a bull to this land that had not felt animal impact for almost 100 years.

DS Family Farms prairie. Photo: Doug Garrison

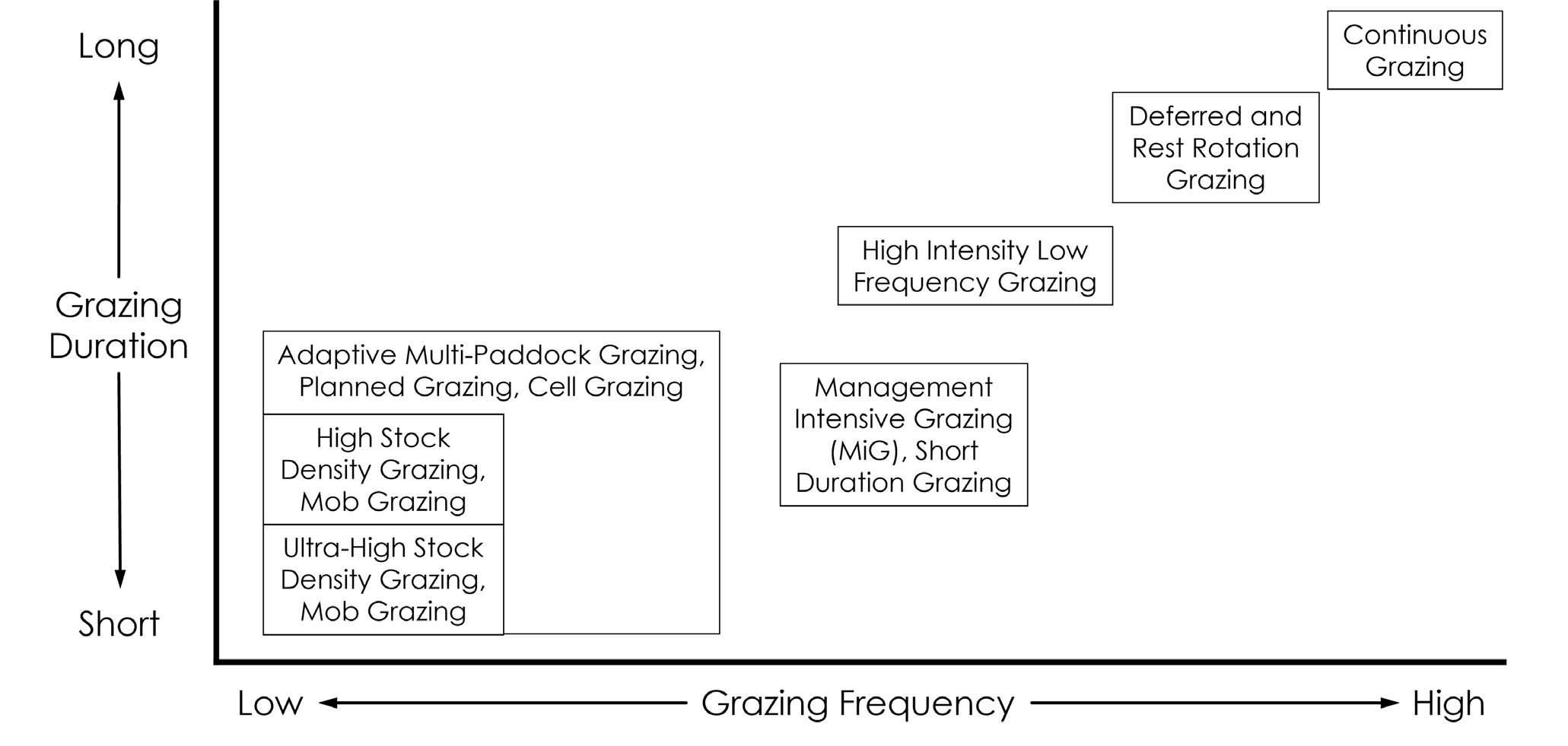

From the start, Doug moved the cattle every day. He learned from Kit Pharo, Joel Salatin, Neil Dennis, and others about the concepts of mob and rotational grazing and has put those into action. Doug set up six main paddocks comprised of two-wire electric cross fencing, each containing one water tank. He then hangs poly wire off that cross fence to set up a less-permanent perimeter within each pasture. This creates a smaller paddock and allows Doug to contain the cattle on a small strip of land. After allowing the cattle to graze for one day, the poly wire is removed and installed further down the pasture, in essence doubling the strip of land. This process is repeated until one entire paddock is grazed without ever cutting off access to the paddock’s water tank. Then, the process is repeated in a different pasture. Doug will put up a poly wire fence to prevent cattle from overgrazing that first strip of land, which requires a different source of water, but cows don’t usually go back to the initial grazed area of that paddock. Doug tries to follow Holistic Management International’s principle to never let the animal take a second bite. Using this technique, 20% of the pasture will have more than one year to rest and recover.

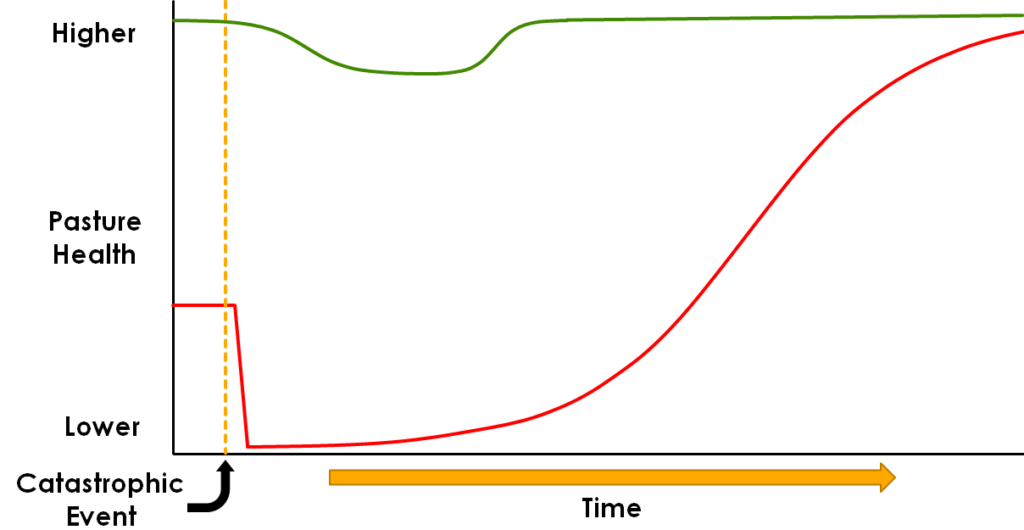

The benefit of this “fresh grass and move” technique is that it automatically gives the pasture long recovery periods. Planning is mostly removed from the equation. Doug used prescribed burning for 10 years before using grazing as a management tool and found differences in biomass production. He has averaged the monthly forage production at three points in the year (beginning of the growing season, summer, and end of the growing season) and found that grazing results in more biomass accumulation on average. There was 100 more pounds per acre at the beginning of the growing season, 200 more pounds per acre during the summer, and 300 more pounds per acre by the end of the year in his grazing operation, compared to when he would burn.

Here it is again:

10-year average total biomass under fire management only = 2,601 lbs. per acre

10-year average total biomass under cattle grazing = 2,899 lbs. per acre

For the data junkies, more information can be found on DS Family Farms website, including information on a cool-season cover-crop trial that benefitted the grazing operation. Blessed with mild winters and 28 to 32 inches of rain a year, DS Family Farms enjoys year-round grazing, which has been enhanced with an annual cool-season grass for winter forage production.

Doug emphasizes that portability and mobility of fencing is key to making his system work. Equally important to success is having a mentor. There are many innovative producers asking questions and providing feedback on the Soil for Water Forum, which is extremely useful, especially if you’re just starting. Additionally, “you have to have a passion and burning in your belly to really do this stuff,” says Doug. “You have to love the animals, and you have to love the outdoors.” The Soil for Water team could not agree more.

Visit DS Family Farms for more information at the following links:

Keep the conversation going at the Soil for Water Forum!