By Justin Morris, NCAT Regenerative Grazing Specialist, and Lee Rinehart, NCAT Sustainable Agriculture Specialist

Did you know that grazing practices could potentially enhance photosynthesis so that plants provide greater quantities of forage? Is it possible for weeds to provide equal or better nutrition than alfalfa? The second session of the National Center for Appropriate Technology’s (NCAT) four-part webinar series, Advanced Grazing for Regenerating Soils and Enhancing Animal Nutrition, addresses these questions by focusing on the plant side of the grazing equation.

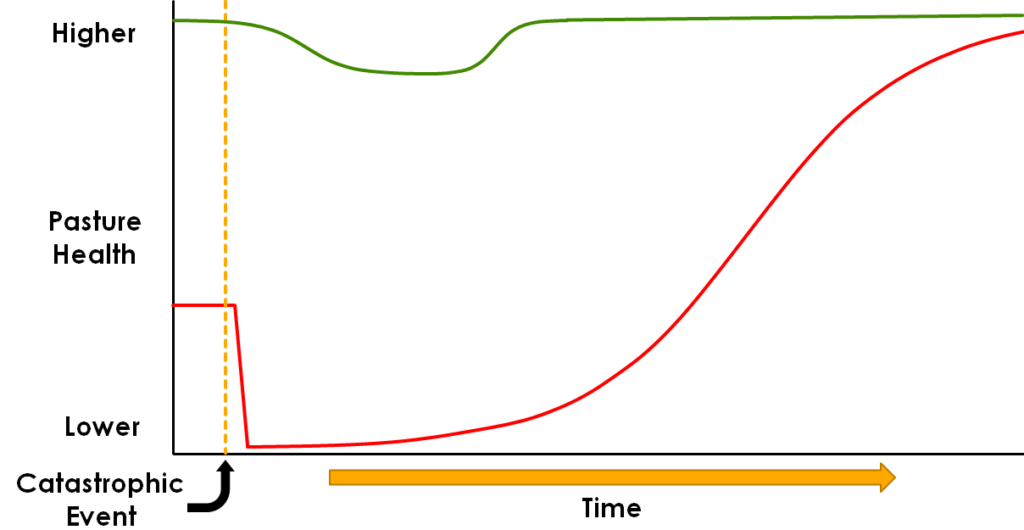

This session starts with a discussion on how a disturbance can improve or degrade plant health and the health of a landscape, depending on the nature of the disturbance. Grazing is a disturbance with four dimensions: timing, duration, frequency, and intensity. Healthy pastures are more resilient to catastrophic events than unhealthy pastures. While catastrophic climatic events cause even the healthiest of pastures (green line) to drop in productivity, the drop doesn’t go as far or last as long compared to unhealthy pastures (red line), as shown in the graphic below.

We also talk about the process of photosynthesis to potentially enhance future plant health and productivity. Overgrazing—grazing a plant before it’s ready to be grazed—prevents plants from achieving a high level of photosynthesis, resulting in very low productivity. When livestock graze plants in the elongation phase, or phase II, plants recover faster from the prior grazing while pasture productivity, root mass, and root exudates increase. The key to prevent overgrazing is to ensure plants are fully recovered before grazing is re-initiated. Overgrazing in the fall is especially detrimental to the following year’s pasture productivity.

Next comes a discussion on how weeds can be valuable as they can access soil nutrients through a deeper, more extensive root system compared to grasses, they can be highly palatable and very nutritious, and they can contain medicinal compounds and dewormers to improve animal health. Weeds can also reduce compaction, remove excess nutrients, provide pollen and nectar for wildlife, and be a food source for birds and mammals. Weed management can happen in a variety of ways, such by focusing on increasing competition with a dense stand of grasses and forbs, delaying spring grazing to let the favorable forages establish well, beginning grazing early in the spring to graze young weeds and annuals like cheatgrass, and deferring grazing until the fall. Grazing severely (very close to the surface) greatly increases the time plants need to recover. Residual carbon above and below the soil surface feeds soil microorganisms, protects the soil from moisture loss, maintains leaf area for photosynthesis, and encourages soil aggregation. Bare ground, low residuals, and too short of a recovery period are invitations to weeds. All plants have toxins—it’s a matter of how much of the plant animals eat.

The session concludes the session with a discussion on the different ways to determine forage yield and initial paddock size. Various methods are detailed, ranging from the simple, such as using a pasture or grazing stick, rising plate meter, or using historic hay yields, to the more complex and time-consuming clip-and-weigh method. There are several ways to determine forage yield and initial paddock size. Paddock size and number of paddocks can be determined easily using simple formulas. Shorter graze periods with longer recovery periods are the key to improving plant health and carrying capacity in environments receiving less than 20-inches of precipitation.

Register for the remaining sessions (May 26 and June 9) here. Watch Session 2 here, and Session 1 here.

Related ATTRA Resources:

Pasture, Rangeland, and Adaptive Grazing

Pastures: Sustainable Management

Why Intensive Grazing on Irrigated Pastures?

This blog is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.