By Linda Coffey, NCAT Agriculture Specialist

As I write this, it’s the last week of 2022. I am thinking about upcoming tax information to file and looking at the barn to see if our hay is going to last longer than winter. I’m looking at our pregnant ewes and wondering: “Was this a good year? Will 2023 be better?”

Last year, the weather was a big factor for us. A cold, wet spring was followed by sudden and intense heat, and cool-season grasses didn’t do well. Then rainfall was sporadic and finally stopped for weeks. The fall was hot and dry and again, and cool-season grasses didn’t do well. We were not able to stockpile fescue because our animals needed the feed. Winter came early, with three snows before Thanksgiving (in Arkansas!), and December brought more snow and brutal cold, so we are going through our hay stash at an alarming pace.

The weather is not in our control and not in yours, either. But we are not helpless. Let’s think about some of the ways we can be sure that 2023 is a better year.

Match the number and kind of animals with your farm resources. This was well discussed on a recent ATTRA podcast by agriculture specialists Lee Rinehart and Nina Prater. Having animals that can thrive in your environment and with your management means better health, fewer problems, and lower cost of production. On our farm, our Gulf Coast sheep certainly thrive and are trouble-free, if you don’t count their disrespect for the electric fence this year. In hindsight, though, when the weather turned hot and dry, it would have been smart to cull the least productive ewes so that the farm could easily support the better ones. Why didn’t we? We are optimists! In 2023, I plan to adjust more quickly to the weather patterns.

Watch body condition on the livestock, especially going into winter, before giving birth, and before breeding. Research has shown that animals kept in moderate body condition have a stronger immune system, get through the winter with less feed and in better shape, have more twins (for small ruminants), breed back more easily, and are better mothers. For beef cattle, body condition score (BCS) has been linked with profitability, as shown in the South Dakota State University article (link). See “Influence of Body Condition on Reproductive Performance of Beef Cows” from October 2020 SDSU Animal Science Department article (Walker, et al.) and pay special attention to Table 2. There, the connection between BCS, pregnancy rate, calving interval, calf gains, weaning weights, calf prices, and finally “$/Cow Exposed” are listed. A BCS of 6 more than doubled the income compared to a BCS of 3. In 2023, I plan to monitor body condition and improve the amount and quality of feed offered at the critical times to boost twinning and milk production, resulting in more productive ewes.

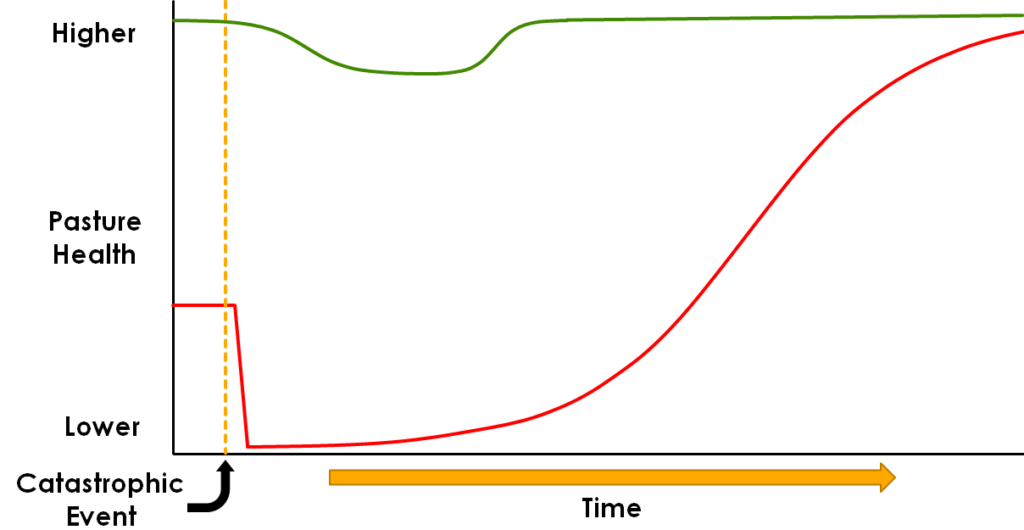

Manage the grazing to improve soil health and forage production. While we cannot make it rain, our management affects how much rain we keep on our farm and how much goes to a creek. Only the water we keep is growing our grass. The great news is that the management needed for soil health also is good for keeping plants healthy and growing, and it’s a continuously improving loop, as Lee and Nina discussed in their podcast. Check out NCAT’s Soil for Water program to learn more about increasing soil health on your farm, and please join the network and the conversation to share your knowledge and your questions. In 2022, our weak link was the aforementioned disrespect for the electric fence. Sheep are not the smartest grass managers; they like the forage short and sweet. Clipping forage too short exposes sheep to parasite larvae, hurts pasture regrowth, doesn’t allow enough energy in the diet thus causing weight loss, hurts soil health by exposing bare ground, leaves us vulnerable to weeds due to the bare ground, and can eventually kill out palatable plants, leaving only the tough, unpalatable ones. These are the cascading effects of grazing too short. Instead, I want to make the decisions about where they are grazing, moving them off before the grass is 4 inches tall and not letting them back until it is fully recovered. I want short grazing periods so that they have less chance of picking up internal parasites and less chance of grazing regrowth. By controlling the grazing, I can influence the total productivity of our farm—plants, soil, and livestock. By providing better nutrition, I can improve gains on lambs and productivity on the ewes, leading to better BCS. In 2023, I plan to work on our electric fence, testing it often and keeping it around 9,000 volts or higher. If I see a rogue animal in the wrong pasture, I will bring it in for retraining in a small lot with hot wire. Repeat offenders belong in our freezer or on a truck headed to a sale.

There is lots more I could decide to do to improve profitability; these ideas really deal with nutrition and caring for the pastures. Of course, recordkeeping, marketing, and planning are vital, and there are useful resources listed below to help with those aspects. Please listen to the podcast Episode 281 about improving profitability and then share your ideas and comments. We all learn best from other farmers, and I look forward to hearing from you. Post your questions and comments on the ATTRA Forum. Best wishes to you and your farm in 2023!

References:

Walker, Julie, George Perry, Warren Rusche, and Olivia Amundson. 2020. Influence of Body Condition on Reproductive Performance of Beef Cows. South Dakota State University Extension.

Fernandez, David. Body Condition Scoring of Sheep. University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. FSA 9610.

Related ATTRA Resources:

Episode 281. Improving Profitability on Livestock Operations

Episode 261. Summer Grazing for Winter Stockpile

Demystifying Regenerative Grazing and Soil Health with Dr. Allen Williams

Small Ruminant Sustainability Checksheet

Beef Farm Sustainability Checksheet (EZ)

Other Resources:

Holistic Management International

This blog is produced by the National Center for Appropriate Technology through the ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture program, under a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. ATTRA.NCAT.ORG.